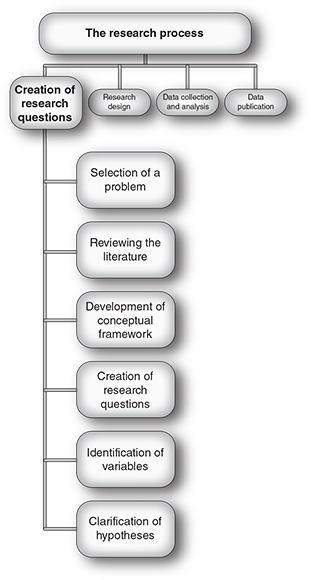

Figure 3.1 Steps for creating research questions.

Problem Selection

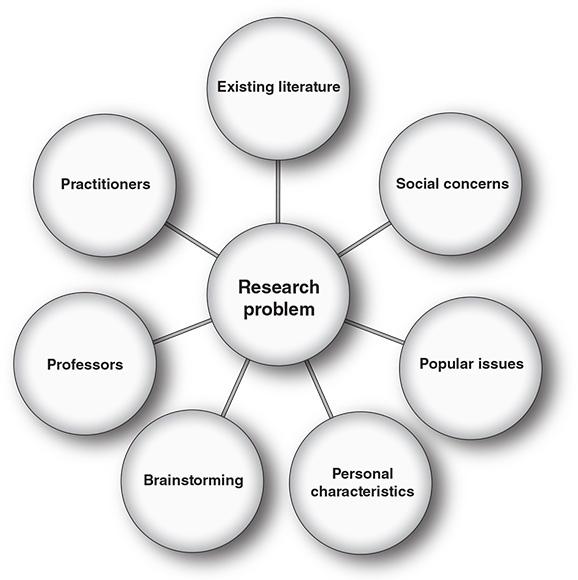

For a sport manager, one of the most challenging stages of the research process is the initial selection of a problem or topic to explore. This stage can be particularly daunting for novice researchers, who may feel that they do not possess enough knowledge about particular sport management topics that need further exploration. It may be encouraging for new researchers to know that this concern can affect all sport management researchers, regardless of how much experience they have with a given topic or problem area, because the more educated one becomes, the more one realizes how much one does not know about various problems both within and beyond the realm of sport. To help you address this challenge, we provided (in chapter 1) a list of research topic areas as a starting point for considering sport management subdisciplines and their context areas. Once you choose a general topic of interest, you can identify potential research problems by examining the existing literature, considering social concerns and popular issues, exploring your personal background, brainstorming ideas, and talking with professors and practitioners. Figure 3.2 illustrates a personalized approach to selecting a research problem.

Figure 3.2 A personalized approach to selecting a research problem. Here are some questions to ask: What issues are emerging in the literature? What research problems could be answered to benefit society; for example, what are the effects of large-scale sporting events on local economies? What contemporary topics are being discussed in the media (e.g., the Olympics)? What experiences from your background might lead to a research study; for example, are you a recreational skier or a sport marketing student? Who can you collaborate with to develop a research problem? What issues are faculty researching, teaching, and discussing? What issues are sport industry professionals facing in the field?

Existing literature. This is perhaps the most obvious source of potential research problems or topics, and you can scan the literature in various ways. For example, if you are comfortable with the general area into which your specific topic falls, you might search electronic databases with specific search terms already in mind. As your search for more specific information progresses, you might narrow or broaden the original search terms depending on the number and quality of sources you find. Alternatively, if you are struggling to select a problem, you might begin your search by perusing printed sources, such as recent editions of peer-reviewed journals; specifically, you might scan the table of contents in various journals until you have identified a number of potential areas of interest. You can then explore these problem areas and narrow your focus. Using existing literature to generate research ideas also enables you to become familiar with previous attempts to address your selected problem, as well as the various approaches that have been used. Remember, too, that many well-written journal articles conclude by identifying avenues for further research about the problem. This is a service to the field and offers ideas for work that you might choose to do.

Social concerns. Research ideas rooted in contemporary social concerns include problems such as the integration of individuals with disabilities into sport and society (Andrew & Grady, 2005; Grady & Andrew, 2003, 2006, 2007; Hums, Moorman, & Wolff, 2003), the impact of diversity in the workplace (Cunningham, 2007; Cunningham & Sagas, 2007; Fink & Cunningham, 2005), and using sport for peace and development (Welty Peachey, Burton, Wells, & Ryoung Chung, 2018; Wright, Jacobs, Howell, & Ressler, 2018). Researchers who select their topics based on social concerns may also enjoy an additional benefit insofar as their research may be a vehicle for social reform.

Popular issues. Research ideas may also be found in the wide range of popular contemporary issues discussed on websites and in newspapers and magazines. If you take this approach, it is crucial to choose a high-quality website or print publication that will have a thorough review of problems that may be of interest. One disadvantage of basing a research problem on popular issues is that they are often so contemporary and novel that they may not have generated a research base yet within the academic literature. In addition, some emerging trends may quickly fade away. Competitive video gaming, or e-sports, has exploded in popularity during the decade of the 2010s, but it is unclear whether it will continue this dramatic growth in the next decade or lose popularity. Yet, popular issues can serve as valuable sources for identifying new areas for discovery, and certain subdisciplines of sport management (e.g., sport law) are more reliant on popular issues than others.

Your own personal characteristics. Sport management researchers hail from a variety of cultures and backgrounds, and their experiences can serve as a platform for research problems. For instance, Todd and Andrew (2008) explored the impact of having satisfying tasks to do and organizational support on the job attitudes of sporting goods retail employees. As the researchers explained, “Given the importance of satisfaction and commitment outcomes to sales force turnover, the possibility that environmental factors in sporting goods retail could alter employee attitudes, and the absence of research in the area, we proposed to extend the literature by highlighting the impact of intrinsically satisfying tasks and perceived organisational support on the job satisfaction and commitment of sporting goods retail employees” (p. 380). Ultimately, the researchers discovered that intrinsically satisfying tasks and perceived organizational support contributed significantly to the prediction of job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment. In other words, sporting goods retail employees who were given more intrinsically satisfying tasks (e.g., tennis-playing employees who are assigned to work in the store’s tennis department) and who perceived organizational support (e.g., employees who believe that the organization has their best interest in mind, supports them, and writes policies that will benefit them) are more satisfied with their jobs and are more likely to want to continue working for that organization. The idea for this particular study was generated through Todd and Andrew’s cumulative work experiences, some of which involved managerial responsibility in the sporting goods retail setting. As they discuss in their article, these work experiences impressed on them the importance of controlling staff turnover, as well as the uniqueness of the context of sport, in the retail setting.

Brainstorming. Generally speaking, brainstorming is a group activity with the expressed purpose of generating a large number of potential solutions to a problem. It can also be a good way to generate research ideas. As ideas and terms emerge during brainstorming, key phrases are written down and then related to each other in generative ways. Discussing ideas with others often helps a researcher develop and refine possible research questions, which is a great advantage of collaborative research. One of the key benefits of attending academic conferences is connecting with colleagues from other institutions, spending time discussing potential ideas for collaborative research.

Faculty. One of the many duties typically assigned to professors is the publication or presentation of scholarly research. As a result, they typically focus on a modest number of research topics and design research projects to facilitate their further exploration. Therefore, although faculty receive their academic credentials from an overall field of study, they usually develop expertise in a few focused areas within that field. With this in mind, one way to generate research ideas is to open a dialogue with professors who hold research interests similar to your own. For students, establishing mentoring relationships with faculty members can be integral in getting their own research started, and participating in a professor’s research project commonly serves as a first foray into becoming a researcher. Others may find a research problem idea in a conversation with a professor or in something a professor discusses in a classroom lecture.

Practitioners. Another potentially valuable source for research ideas is sport management practitioners, who can often identify applied problems within the field that they have encountered through their work experiences. In a critique of the existing sport management research at the time, Weese (1995) lamented that sport management scholars were not serving the needs of practitioners, and unfortunately, much of his critique remains valid more than two decades later. By involving practitioners in topic selection, you can help ensure that your study will be pertinent to those working in the field. In one example, McEvoy and Morse (2007) examined how attendance at an NCAA Division I men’s basketball program’s games was affected by whether the game was televised. The study originated in a conversation McEvoy had with the athletic director of an NCAA Division I school, who said that he believed televising games would cause potential spectators to stay home and watch games on television rather than purchase tickets and attend the games in person. McEvoy, in contrast, hypothesized that televising the school’s games would expose potential spectators to the product, serve as a 2-hour advertisement of sorts for the school and its athletic teams, and potentially add a layer of excitement to the game itself because of the presence of television. McEvoy and Morse designed a study to test the relationship between game attendance and the televising of games while controlling for other variables that might affect this relationship, such as the strength of the opponent and the day of the week. They found that attendance increased by 6.3 percent when games were televised, thus illustrating how involving practitioners in the process of generating research problems can lead to research that is practical and actionable in the industry. In this example, practitioners considering whether to televise their games were able to rely not only on their hunches and instincts but also on data-based research in making such a decision.

After assimilating a number of sources regarding a potential research topic, researchers sometimes find that a past study has already addressed their original research idea. Such a discovery, however, does not necessarily indicate that further research is moot in the chosen area. Veal (1997) suggested some ways in which researchers can build on earlier research in the field. First, the results of any study may vary according to the geographic background of the sample; for example, an analysis of cricket fans’ attitudes in Australia is not particularly generalizable to cricket fans in Canada. Indeed, several sport management studies have focused on cross-national differences found in samples from two different countries on topics ranging from leadership behavior (Chelladurai, Imamura, Yamaguchi, Oinuma, & Miyauchi, 1988) to the consumption motivations of MMA fans (Kim, Andrew, & Greenwell, 2009). Therefore, a researcher can consider conducting a new study using fans from a different targeted geographic area. Second, past studies in a particular problem area may have devoted less attention to some social groups than to others. The impetus for analyzing neglected social groups may be to highlight an underrepresented social group or to respond to changing societal demographics. For example, a growing Latino population in the United States has recently generated a stream of sport marketing research about patterns of sport consumption by Latinos (Harrolle & Trail, 2007; Mercado, 2008). Furthermore, determining the applicability of past research (or the lack thereof) to particular social groups can often lead to the advancement of theory in the field.

Another way to complement past research is to offer a temporal update of an earlier research project. This approach allows a researcher not only to provide an up-to-date snapshot of current trends in the area but also to initiate data comparisons between past and present research. Significant events in history can also provide a supportive rationale for a modern treatment of earlier research. For example, a researcher interested in the perceived security of spectators at sporting events might not feel comfortable relying on results reported before the tragic events of September 11, 2001, in the United States, because that event has ramped up the need for security at major events held throughout the world.

Fourth, researchers may identify existing theories outside the realm of sport and propose to test them in the unique context of sport. Such a contextual approach can also be used to revisit existing research under modern theoretical paradigms to determine whether the new theoretical approaches provide greater explanatory power.

A final approach whereby researchers can build on earlier research is to adapt a novel method of analysis to explore a phenomenon. For example, a researcher might follow up a previously published qualitative study with a quantitative approach that focuses on testing theory with a larger sample. Researchers can also help confirm findings generated by earlier research by using alternative designs (e.g., using a survey to follow up on findings from in-depth interview data).