The fastest muscle movement in the human body is a saccade at 1,000 degrees per second (Holmqvist & Nystrom, 2011). The purpose of a saccade is to move the eye from one relevant location (or cue) to another. An athlete’s ability to track objects and react appropriately develops with experience and at an individualized pace. Visual attention, perceptual information processing, and response selection can be disrupted by anxiety and distraction. Training to improve the allocation of attentional resources can enhance the development of these skills and protect them against the effects of pressure (Vine, Moore, & Wilson, 2014).

Benefits of Visual Search Assessment

Effective use of visual gaze behaviors (see table 10.2) and, in turn, the assessment of perceptual-cognitive skills, provides the following benefits:

- Anticipation: Looking at the right spot at the right time and making sense of what is seen enhances the ability to predict future events (Farrow & Abernathy, 2002; Savelsbergh, Williams, van der Kamp, & Ward, 2002).

- Attention: Efficient use of attentional resources involves focusing on the most important cues while ignoring distractions to take in the minimum amount of essential information. This results in the most efficient processing (Williams & Davids, 1998).

- Memory:Synthesis of past events into meaningful chunks of information enables athletes to employ effective strategies and tactics (Abernathy, Baker, & Cote, 2005).

- Pattern recognition:The ability to read plays based on experience (North & Williams, 2008) allows athletes to synthesize patterns and learn from them.

- Problem solving: The ability to conceptually organize thoughts based on visual information processing influences athletes’ ability to determine what has worked and what hasn’t (McPherson & Kernodle, 2003).

- Decision making: Athletes with effective perceptual-cognitive skills can read, anticipate, and make accurate decisions quickly (Vaeyens, Lenoir, Williams, Mazyn, & Philippaerts, 2007).

- Situational awareness: The ability to perceive and understand the environment (Caserta & Abrams, 2007) improves as athletes know what is visually important and what to ignore.

- Motor efficiency: The result of effective perception and cognition in sport is often motor efficiency (Williams & Ericsson, 2007).

- Stress reduction: A further benefit of effective perceptual-cognitive skills is reduced stress (Gerstenberg, 2012). Being more focused and reducing information processing can lead to a cascading reduction in stress (Vickers & Lewinski, 2012).

- Alertness and resilience: The ability to stay alert over time is an important benefit of perceptual-cognitive skills. In any situation with a potential for fatigue, the more efficient the perceptions, cognitions, and motor responses, the greater the alertness and resilience (Williams, Hodges, North, & Barton, 2006).

Eye Tracking

Unlike biomechanical changes, which are readily observable, visual and cognitive processes are not so easily scrutinized. An eye tracker is a special pair of glasses that records athletes’ point of gaze upon the environment, taking pictures of the location of the gaze at various frame rates (e.g., 60 times per second), similar to a camera. Eye-tracking technology enables us to make three types of visual feedback assessments.

Gaze Location

An eye tracker examines the location of a person’s focal vision (gaze point) within an environment to determine if the subject is attending to the appropriate cues (see figure 10.4). For example, research has demonstrated that looking at the contact point when returning a serve in tennis assists in ball tracking (Murray & Hunfalvay, 2016). In baseball, the pitcher’s hand positioning on the ball helps hitters determine the type of pitch that will be thrown (Takeuchi & Inomata, 2009).

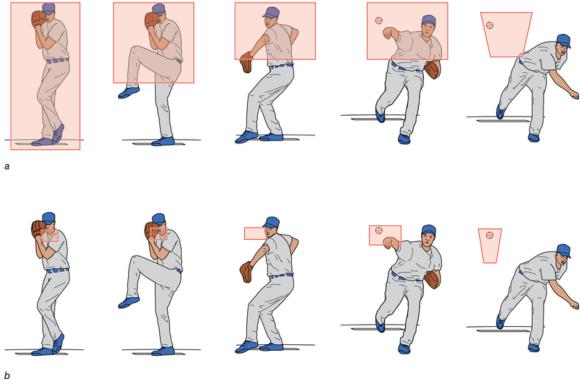

(a) Minor League Baseball aggregate visual search cues versus (b) Major League Baseball aggregate visual search cues. Major leaguers demonstrate attention to fewer and more localized visual cues.

Assessment of visual feedback gaze location using eye trackers is based on research using temporal occlusion (Farrow, Abernathy, & Jackson, 2005), where the task being viewed is stopped at various points before completion and athletes are asked to extrapolate information about what will happen in the future, such as the direction a ball will travel. Visual feedback is also based on cue occlusion (also called spatial occlusion) research (Muller & Abernathy, 2006), where important cues are blocked from view to determine their impact on performance. These assessment paradigms measure performance outcomes using additional tools such as pressure-sensitive floor mats and infrared beams that detect response time (Williams & Ericsson, 2005).

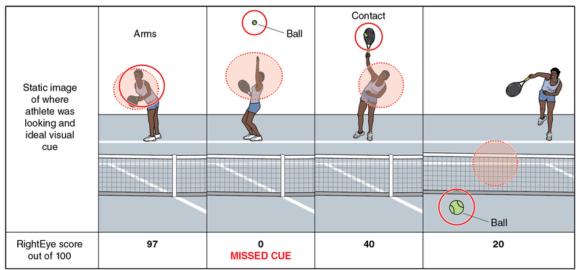

Common assessments of gaze error include missed cues, scattered visual search, and late tracking. Missed cues (see figure 10.5) are often caused by a lack of perceptual-cognitive expertise or a failure to understand what the cue reveals, why it is important, and how it can be used to improve performance.

Gaze location and important visual cues. Solid circles represent important visual cues. Dotted circles represent the athlete’s actual gaze location. Convergence of the two is scored out of a possible 100. Here, the missed cue in the toss phase results in failure to target the contact point and late ball tracking.

A second common error in gaze location is a scattered visual search pattern. Figure 10.4a demonstrates the wider visual search area of a less experienced baseball player. Research demonstrates that experts exhibit fewer fixations of longer duration compared with less skilled performers (Gegenfurtner, Lehtinen, & Säljö, 2011; Mann, Ward, Williams, & Janelle, 2007). Less skilled athletes who display a scattered search pattern end up processing too many cues because they are unsure where to look and what is important.

Late tracking is another common error in gaze location. This occurs especially in fast-moving, open-skilled sports when athletes start late and do not have time to catch up. This can be due to a lack of expertise or a lack of attention or readiness. Late tracking in the beginning of a sequence has negative consequences that multiply further along the biomechanical phases.