Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to

- distinguish between job simplification, job rotation, and job enlargement;

- understand the concept of job enrichment;

- explain the various attributes of jobs and their motivational properties;

- understand the concepts of interdependence among tasks and the variability of tasks;

- distinguish between standardization, planning, and mutual adjustment as methods of coordinating jobs; and

- select an appropriate method of coordinating tasks based on their interdependence and variability.

It is not uncommon to hear people say the following things about their jobs: "A job is a job is a job." "I love my job." "My job is not a great one, but it pays well." "My job is like any other, but the people I work with are absolutely wonderful." "My job is okay, but my supervisor is intolerable." For some people, a job may be interesting and satisfying, and these jobs may serve as a retreat from the worries and turmoil of the outside world. Others may perceive their job as the penalty they pay for the enjoyment of life outside the workplace.

These different reactions can be found in all kinds of jobs. That is why we have the phrases "white collar woes" and "blue collar blues." At the same time, these reactions highlight the fact that not all jobs are alike. Jobs can differ in their content (which may be, for example, either exciting or tedious) and in their context (e.g., the work group, the leader). Similarly, the rewards of task performance can be either intrinsic (e.g., the job is challenging) or extrinsic (e.g., the job pays well). These concepts were introduced in chapter 8 in the discussion of Herzberg’s (1968) two-factor theory. In this chapter, we elaborate on the nature of a job.

First, we must briefly define the concepts of job design. McShane and Von Glinow (2010) define job design as "the process of assigning tasks to a job, including the interdependencies of those tasks with other jobs" (p. 175). This definition, in turn, implies that a job is a set of tasks performed by a person.

Theorists and practicing managers have tried to modify job design to increase worker motivation and productivity. This chapter outlines four of the general procedures that have been used: job simplification, job rotation, job enlargement, and job enrichment. Because job enrichment is the superior job design strategy, it is addressed in more detail.

Job Simplification

Job simplification was initiated in the early part of the 20th century by industrial engineers whose intent was to make each job as simple and specialized as possible in the interest of improving efficiency. These engineers even studied the time taken for each motion in performing a task and tried to simplify those motions. These time - motion studies permitted the engineers to break down tasks into activities and specify in detail how each activity should be carried out. This approach is still found in the assembly-line operations adopted by many manufacturing firms.

In a system of specialized and simplified tasks, employees have little room to vary from specified routines. One potential advantage of job simplification is that of increased economy of operation. This increase is achieved because simplified jobs promote specialization, which, in turn, increases productivity. Another advantage is that simplified jobs can be staffed by low-skilled employees who require little training and are transferable from one job to another. Furthermore, management can easily monitor productivity in these simplified jobs.

On the other hand, several potential reactive outcomes undermine the potential advantages of job simplification. Because job simplification makes a job routine, monotonous, and boring, workers eventually begin to dislike the job; as a result, absenteeism and turnover increase. In addition, even when workers attend work, they may not put forth their best effort, and they may be prone to making mistakes. However, job simplification typically disregards psychological implications such as boredom and isolation.

Rees (1996) remarked that, too often, job design is handled through a Procrustean approach. Procrustes was a legendary figure in Greek mythology who had a special bed and was obsessive about having guests fit into it exactly. In fact, he would take drastic measures to ensure that his guests fit the bed - for example, cutting off their feet if they were too long - but showed little regard for adjusting the bed to match his guests. The moral is that jobs can be designed with little or no thought given to matching a job with an individual. This approach assumes that people can always be found who can be made to fit the job, however badly it may be designed. Although this assumption is not so widely held in modern times, managers must still make a point to assess which employee’s abilities, personality, and values (as discussed in chapters 5 through 7) are consistent with simplified jobs.

Job Rotation

In order to counter the negative ramifications of job simplification, researchers have advanced two strategies (Saal and Knight 1995). The first strategy is job rotation - that is, moving workers periodically from one job to another. For example, two workers in a fitness club might alternate each week or month between the job of receiving clients and that of facility and equipment maintenance. Job rotation may have the immediate effect of offering excitement because of the novelty of the different job, location, and work group. Once the novelty wears off, however, workers may still be alienated from their jobs if each of the jobs they move into is simplified, routinized, and boring. Even so, due to the variety involved, rotating into different jobs is more motivational than performing one simplified job.

Job rotation offers another advantage in the form of training the workers: "It allows workers to become more familiar with different tasks and increases the flexibility with which they can be moved from one job to another" (Schermerhorn, Hunt, and Osborn 1997, p. 155). This flexibility is particularly significant when someone is absent (e.g., due to sickness or injury).

Job Enlargement

Another strategy for motivating workers is to enlarge their jobs. That is, instead of being locked into one specialized and routinized job (e.g., filing), a worker is asked to do more things (e.g., data entry, social media monitoring, and phone answering). In the previous example of a fitness club, the two employees may both be involved in facility and equipment maintenance as well as reception work. As in job rotation, job enlargement may have only minimal effect on workers’ motivation and satisfaction as long as the added tasks are still simplified. Again, however, the opportunity to do a variety of jobs is better than doing just one simplified task.

Management may undertake job enlargement either in the belief that it will satisfy workers’ needs or because the additional work is best assigned to those who do similar work (Saal and Knight 1995). Therein lies a problem. Even when managers undertake job enlargement with the good of workers in mind, workers may perceive it as a management tactic to extract more work from them. One way in which managers can counteract negative perceptions is to clearly articulate the reasons for job enlargement and to explain that the process results in a mix of tasks but not in more work. Furthermore, if the workers themselves are involved in the process of job enlargement, they are likely to better comprehend the rationale for it and accept the decision.

Job Enrichment

Recall that Herzberg’s (1968) motivation - hygiene theory proposed that a job’s content, rather than its context, best serves an individual’s higher-order needs. In addition, the intrinsic rewards of working are derived more from the job itself than from other factors. This theory carries the practical implication that jobs need to be designed in such a way that more of the true motivators (i.e., sources of higher-order need satisfaction) are present in job performance.

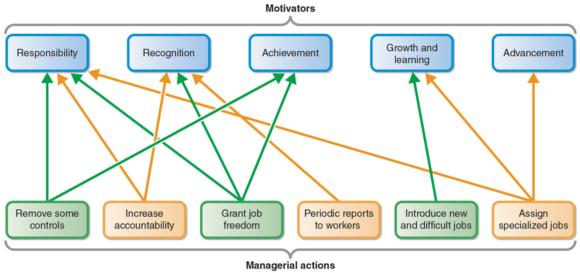

According to Herzberg (1968), the issue of job meaninglessness is addressed neither by job rotation nor by job enlargement. From this perspective, these efforts either move a worker into different meaningless jobs or heap more meaningless jobs on the worker. Indeed, Herzberg viewed job rotation as substituting one zero for another and viewed job enlargement as adding one zero to another. Therefore, his concept of job design focuses instead on "vertical loading," or job enrichment. More specifically, figure 10.1 shows Herzberg’s six principles for enriching jobs and their connections to the various motivators involved.

Principles of vertical loading.

Based on Hersberg 1987.

As shown in figure 10.1, the purposes of vertical loading are to

- make the worker feel responsible for the job,

- enable the worker to experience achievement and growth in a challenging job, and

- allow the worker to gain recognition (both internal and external) for a job well done.

These purposes can be achieved by allowing workers more authority to decide how they carry out assigned work, making them more responsible for their work, and providing them with fast and accurate feedback. This approach minimizes monitoring and directing by supervisors. Vertical loading of a job also involves assigning more new - and more difficult - jobs to workers. In the earlier example of the fitness club, the two workers might be allowed to decide between themselves how to fulfill the responsibilities of reception and facility and equipment maintenance.

Herzberg (1974) pointed out that an enriched job is characterized by the following features.

- Direct feedback:A worker should receive immediate and concrete feedback when his or her work has been evaluated. In some cases, the feedback can be built into the job itself. For example, workers in a professional sport franchise who sell season tickets get their feedback via an electronic survey as they sign up a fan.

- Client relationships:Herzberg held the view that contact with clients is itself an enriching experience. As noted in chapter 1, sport management is concerned mostly with the production of services, and that process requires client participation. From this perspective, sport management jobs that involve interaction with clients, both in person and through social media, are by definition enriched. Some research (Chang and Chelladurai 2003; Osborn and Stein 2016; Smith 2001)has shown that workers view their interaction with clients as more important or more satisfying (or both) than any other aspect of their job.

- New learning:An enriched job provides opportunities for gaining knowledge and learning new ways of doing or managing things. For example, when a student intern in an athletics marketing department is assigned progressively more challenging jobs, the student is enabled to learn more about marketing operations.

- Control over scheduling:Job enrichment may also allow workers to schedule their own work. Though not possible in all cases, it can be achieved in most cases through the use of work schedules such as flextime (discussed in chapter 14). For example, this attribute is characteristic of the job of a university professor, whose major responsibilities including performing and publishing research. The university does not say when or where the research should be conducted; rather, professors set their own schedules for research work.

- Unique expertise:"In this day of homogenization and assembly line mentality, when everyone is judged on sameness, there exists a countervailing need for some personal uniqueness at work - for providing aspects of the job that the worker can consider as doing [his or her] own thing" (Herzberg 1974, p. 73). It is implied here that the worker will be able to bring personal ability and expertise to bear on the assigned work. For example, younger employees often come into sport and recreation organizations with distinctive abilities in technology and social media, and managers should capitalize on this expertise.

- Control over resources:Another feature may be the worker’s control over money, material, or people. For example, the secretary of a sport management department may be permitted to handle the budget for supplies as he or she deems fit. Similarly, the marketing assistant in an athletics department may be empowered to manage interns without interference from supervisors.

- Direct communication authority:In an enriched job, employees are given the authority to communicate directly with those who use their outputs, or those who provide inputs to the job, or both. For instance, a manager in a city recreation department would be permitted to communicate directly with suppliers of sport equipment and community groups who have a stake in the department’s affairs.

- Personal accountability:With all of these features built into a job, it stands to reason that the job incumbent is held personally accountable for his or her performance. For instance, a worker in the ticketing department of a professional sport franchise may redesign the way in which he or she carries out the job, including the scheduling of work hours. Such authority is accompanied by accountability for ensuring that the work does not suffer in any way.

Save