The following section provides an overview of implications for teaching physical education to children with ASD - specifically, assessment, activity selection, and instructional and management techniques.

Assessment

One method that has been proven helpful in assessing students with ASD is the system known as ecological task analysis (Carson, Bulger, & Townsend, 2007). Within the model, the instructor examines the interaction of three factors: the student, the environment, and the task. To derive a good understanding of the student, the assessor should seek information from several sources, including parents, teachers, therapists, and aides. One should fully understand reinforcers and modes of communication before attempting to assess the child. The assessor should also spend time developing a rapport with the child before assessment. When beginning the assessment, it is important to start with activities the child understands and is able to perform and then move on to more difficult tasks. It is important also to understand qualities that inhibit or enhance performance. This approach allows for early success and better compliance throughout the assessment.

The second factor that needs to be considered is the task. To determine if the task is appropriate, consider the following questions: Is it age appropriate? Is it functional? Will the information gained assist in the development of individualized education program (IEP) goals and objectives? Will the information be used for program development and instruction? If the answer to any of these questions is yes, then the task being assessed is appropriate. To assess the task, the assessor might use a task analysis approach in which requisite skills are identified and either further broken down or assessed as a whole. For example, in assessing soccer skills, the assessor would determine the requisite skills for soccer (e.g., dribbling, passing, trapping, shooting). Each of these skills could be broken down into components assessed separately, or the skill could be assessed as a whole. Once the assessment is complete, the information gleaned can be used to develop goals and objectives based on unique needs, serve as a basis for instruction, and aid in activity selection.

Finally the instructor needs to consider the environment. Keeping in mind that children with ASD might be hypersensitive to environmental stimuli, the instructor should provide an environment with limited distractions and focus on one task at a time. In the soccer example, the instructor can provide different-size balls, different-size goals, and different surfaces for performing the task. After considering the individual student, the task, and the environmental parameters involved, the instructor observes the student’s behavior and preferences and documents his choices. These choices serve as a baseline and a springboard upon which to teach.

Activity Selection

When selecting activities for children with ASD, the most important consideration is the needs and interests of the learners and their families. In addition, the functional value of the activity should be taken into account. Activities that have a high probability of success for children with ASD are generally more individual, such as swimming, running, and bowling. However, no one should assume that children with ASD cannot participate in and enjoy team sports. Team sports might need modifications to enhance success, but all children should have the opportunity to explore a range of physical education activities.

The learner’s age must also be taken into account. Both developmental appropriateness and age appropriateness should always be considered when selecting activities. Although elementary-aged children spend a great deal of time learning and improving their fundamental motor skills, it would be inappropriate to focus on such skills at the middle school or high school level. When selecting activities, instructors should also consider family and community interests. Does the child come from a family that enjoys hiking or skiing? Or is the family more involved in soccer or softball? Considering these factors helps shape the activity selection so that the child with ASD can more fully integrate within the family and community.

One form of movement, known as sensorimotor activities, can be especially beneficial to students with ASD. These activities are designed to stimulate the senses with a focus on kinesthetic awareness, tactile stimulation, auditory processing, and visual - motor coordination. Kinesthetic awareness deals with the relationship of the body to space. Examples of kinesthetic activities include jumping on a trampoline, crawling through tunnels, jumping over a rope, and rolling down an incline mat. Tactile stimulation can be enhanced by having the child interact with objects, such as balls with various sizes, shapes, and textures. Auditory processing can be enhanced through the use of music and songs that instruct the child in a sequence of movements. Finally, visual - motor coordination can be strengthened through playing an array of games that require tracking, such as kickball, softball, soccer, or lacrosse.

Instructional and Management Techniques

Teaching students with ASD is not unlike teaching other children. Teachers need to establish rapport with students, develop trust, relay information in a clear and concise manner, and provide reinforcement and feedback to help shape appropriate motor and social behavior. Specific strategies that prove helpful in instructing and managing students with ASD include the use of picture and communication boards, the consistent use of structure and routines, and the use of natural cues in the environment to facilitate the acquisition and execution of skills. Other methods include the correction procedure rule and parallel talk. The correction procedure rule is a system used when inappropriate skills or social behaviors occur. Here, the instructor takes the child back to the last task that was done correctly in an effort to redirect the inappropriate behavior. Parallel talk is a system in which the instructor talks through the actions that are occurring - for example, "Juan is dribbling the basketball" - which aids in the understanding and purpose of actions. In addition, teaching to the strengths of learners by considering their preferred learning modality will also prove helpful in teaching students with ASD. Finally, the value of using support staff and peer tutors should not be underestimated in teaching students with ASD. Each of these strategies is more fully explained next.

Picture and Communication Boards

One of the most common and most successful methods used to teach children with ASD is the use of picture and communication boards. Types of pictures include photographs, lifelike drawings, and symbolic drawings. Some children may not yet understand pictures and may need objects to represent them, such as dollhouse furniture or small figures of objects. When pictures are used, it is best to have only one item in the picture because children with ASD have a tendency toward overselectivity, meaning that they are not able to screen out irrelevant information. Teachers should help students focus on the most relevant information. For example, if a child is working on basketball skills, it may be preferable not to use a picture of a basketball court with students playing on it because there is too much information in the picture, making it difficult for the child to screen out irrelevant information. Pictures can also be arranged to create a daily, weekly, or monthly schedule. Boardmaker, as described earlier, is one of many commercial software programs that can help create picture boards using universally accepted symbols to depict events and actions.

Routines and Structure

Establishing routines and structure aids in managing and instructing students with ASD. Children with ASD often demonstrate inappropriate behavioral responses when new or incongruent information is presented in a random or haphazard manner. Routines with set beginning and end points allow for more predictability and help to reduce sensory overload. Routines are also useful in introducing new information or behaviors. Keeping some information familiar and gradually introducing new information helps students respond appropriately. Routines also help to reduce verbal directions and allow children to work independently.

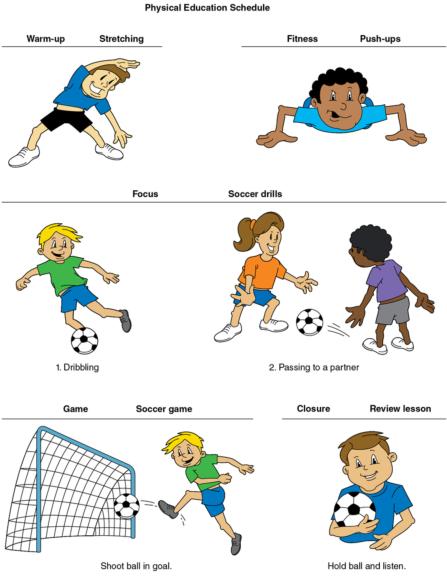

The following scenario illustrates a typical routine that incorporates pictures and can be useful in physical education. Before Justin goes to physical education class, a classroom teacher gives him a picture of the physical education teacher and says, "Justin, it is time for PE." The picture of the physical education teacher allows Justin to understand what is going to happen next. When the class enters the gym, Justin gives the picture card to the physical education teacher. The physical education teacher then uses a communication board with pictures to relay to Justin the lesson from start to finish. For example, a picture of a child stretching could indicate the warm-up, and a picture of a child doing curl-ups could indicate the fitness portion of the lesson. Further, the specific focus could be identified, as with a picture of a soccer ball. Finally, goalposts can be used to indicate the game activity. Figure 10.2 presents a sample schedule for a physical education lesson. The components of the schedule can remain the same, but the actual activities can be manipulated to prepare the child for the daily lesson. When using words instead of pictures, the words can be erased after the task is completed. This system allows students to understand that the activity has ended and the next activity will soon begin.

Physical education sample pictorial schedule. The pictures allow the student to understand what is going to happen in the lesson from start to finish.

As noted previously, children with ASD have difficulty with sensory overload. When they are entering a new environment, such as a gym, the atmosphere may create extreme sensory overload. Structure helps alleviate this stress by creating environments that are easily understood and manageable. In physical education, teachers can structure their space so that the environment is predictable. First, the teacher needs to identify for the child where activities are done (in the gym, on the field, on a mat), where things are located (balls in bin, ropes on hangers, rackets on hooks), and how to move from one place to another (rotating stations, rotating positions, moving from inside to outside). Second, the teacher needs to establish concrete boundaries. For example, if a child is to remain on one-half of the field, cones indicating the halfway point should be in place. Labels can also help organize space. For example, equipment boxes should be clearly labeled so that the child can easily retrieve and put away equipment.

At the conclusion of the lesson, the physical education teacher should have a consistent cue to transition the child back to the classroom. This could be a picture of the classroom teacher or a desk. Forewarning is another effective way to transition a child back to the classroom. For example, the teacher might say, "Justin, in three minutes PE will be over." This helps the child better understand time and prepare for the change in routine. A second warning might be given at 2 minutes and a third at 1 minute. Through proper preparation, anxiety levels are reduced because the child begins to understand that a change in the task will occur after the 1-minute signal from the instructor. Again, the child must understand what will be happening next. When he arrives back in the classroom, physical education can be crossed off his daily schedule and he can begin the next activity on the schedule.

The implementation of routines and structure might at first seem time-consuming for the teacher. However, once these systems are in place, dramatic improvements in behavior and participation usually occur, making the extra time and effort worthwhile.

Natural Environmental Cues and Task Analysis

In teaching new skills to children with ASD, instructors are urged to use natural cues within the environment and to minimize verbal cues. If the goal is for the child to kick a soccer ball into a goal, the natural cues would be a soccer ball and a goal. To achieve the desired objective, the instructor might need to break the task down into smaller steps or task analyze the skills. For example, shooting a soccer ball into a goal might involve the following steps: (1) Line the child up at the shooting line; (2) place the ball on the shooting line; and (3) prompt the child to take a shot. One may break the skill down further by placing a poly spot in front of the child to initiate a stepping action with the opposite kicking foot and prompting the child with either a verbal cue or physical assist to use the kicking foot to make contact with the ball. The degree to which skills should be task analyzed depends on the task and the learner.

Demonstrations also prove helpful in the acquisition of new skills. If the child performs the task correctly, the lesson should continue. For example, the teacher might teach the child how to stop a ball being passed to the shooting line. If the child is unsuccessful in shooting the ball toward the goal, the teacher could use physical assistance to help her gain a better understanding of what the task requires, allowing her to repeat the task until no physical assistance is needed. Once the child has performed the task correctly, the teacher would move on to the rest of the lesson. Figure 10.3 depicts a child working on soccer skills with assistance.

Shooting a soccer ball into a goal can be broken down into steps. Here the child is taking step 3, with the assistant prompting the child to take a shot.

© Cathy Houston-Wilson

Correction Procedure Rule

Another effective technique in instructing children with ASD is the correction procedure rule, which one applies by taking the child back to the last component of the skill done correctly. Using batting as an example, say a child maintains a proper batting stance and properly swings the bat at the ball but then runs to first base with the bat. In this case, following the correction procedure rule, the instructor would ask the child to repeat the swing and then physically assist her in placing the bat on the ground before running to first. The instructor returns the child to the last correct response before the incorrect response. The application example is another scenario in which the correction procedure rule can be used.

Application Example

Importance of Visual Cues in Learning a New Task

Setting

A physical education class is working on a tee-ball unit.

Student

Kiera, a seven-year-old girl with autism in elementary physical education class

Task

Learning how to hit a ball off the tee and running to first base

Issue

Kiera’s physical education teacher, Mr. Greer, has been teaching her how to play tee-ball. They have practiced swinging the bat at the ball (in a hand-over-hand manner), making contact with the ball, putting the bat down, and running to first base. It appeared that Kiera had the hang of the skill, so Mr. Greer allowed her to bat independently. Kiera stood in the ready position; Mr. Greer placed the ball on the tee and took a step back. Just then a gust of wind came, and the ball fell off the tee. Kiera immediately placed the bat on the ground and began running to first base even though she did not make contact with the ball. This showed that Kiera still did not understand the purpose of the game, which was to contact the ball with the bat before running.

Application

Mr. Greer used visual cues to create a positive learning environment by doing the following:

- Mr. Greer demonstrated to Kiera what to do if the ball fell off the tee. Mr. Greer put the ball on the tee loosely so that it would fall off. When the ball fell off, he picked up the ball, replaced it on the tee, and struck it with the bat.

- Mr. Greer then signaled to Kiera to try. Again he placed the ball loosely on the tee and gave the bat to Kiera.

- The ball fell off the tee and Kiera picked up the ball and replaced it on the tee. She then struck the ball and ran to first base.

This example illustrates the need for students with autism to see and understand a task. In no way was Kiera being uncooperative or off task. She simply did not understand the task. When she understood the task, she was able to participate in the game independently.

Kiera practices her swing in tee-ball.

© Cathy Houston-Wilson

Parallel Talk

To promote language and skill acquisition, instructors are encouraged to embed language throughout the lesson. One way to accomplish this is using parallel talk, in which the teacher verbalizes the actions of the learner. For example, if Marci is rolling a red ball to the teacher, the teacher would say, "Marci is rolling the red ball." Parallel talk can also help children associate certain skills with their verbal meaning, such as spatial concepts (e.g., in, out, under, over) and motor skills (e.g., dribbling, shooting, striking). Another way to foster language acquisition is to create print-rich physical education environments. Pictures, posters, and action words should be displayed prominently around the gym. Labeling the action as it is being performed helps students acquire both receptive and expressive language skills and attach meaning to actions.

Learning Modalities

Learning modalities, or learning styles, refer to the way in which students learn best. The three common categories of learning include auditory, motor, and visual. Auditory learners tend to learn by following commands or prompts and may be easily distracted by background noise. Children who are motor or kinesthetic learners tend to learn by doing. They are active learners and would rather do than watch; they enjoy hands-on projects. Children who are visual learners tend to learn by watching and looking at pictures, and they can be easily distracted by surrounding activities and noise. Research indicates that students with ASD tend to be visual learners (Sicile-Kira, 2014), although all learning modalities should be employed from time to time. As indicated previously, the use of pictures and communication boards is by far the most effective teaching strategy used to communicate with and teach students with ASD.

Support Personnel

Teachers should take advantage of support personnel to assist them in implementing programs. Teaching assistants, paraprofessionals, and peer tutors are all valuable resources that can help in providing individualized instruction to students with ASD in physical education. Teachers can request support personnel through the child’s IEP as a necessary component to support the learning of children with ASD.

Save