Fitness Program Decisions

This chapter has addressed the guidelines supported by the AHA and ACSM concerning when physician consent is necessary before a participant undergoes fitness testing or begins an exercise program. The following section discusses additional criteria to consider as the fitness professional decides which of the following actions to pursue:

- Immediate referral for physician consent or proper medical consultation

- Admission to one of the following fitness programs:

- Clinic-based supervised exercise program

- Appropriately prescribed exercise under the supervision of a fitness professional

- Vigorous-intensity exercise

- Any unsupervised physical activity

- Educational information, seminars, or referral to other health professionals

Fitness professionals will encounter individuals who are on the verge of meeting the criteria for moderate or high risk but are not quite there. Do they require physician consent? Should they exercise in a supervised program? The following section helps resolve these dilemmas.

Determining If Referral to a Supervised Program Is Necessary

The fitness professional should consider the participant’s health status and desired activity level to determine whether referral to a supervised exercise program is necessary. A supervised program, sometimes referred to as a phase III program, entails professionally qualified staff who have academic training in and clinical knowledge of monitoring special populations classified as high risk (e.g., individuals diagnosed with cardiovascular, pulmonary, or metabolic disease) (1-3). These types of programs are also better suited for individuals with special conditions (e.g., emphysema, chronic bronchitis, cancer, epilepsy) that warrant additional supervision by medically qualified personnel (e.g., nurses or registered clinical exercise physiologists) who have experience with special populations.

Section 2 of the HSQ helps identify health conditions that require constant supervision. For example, the HSQ of a prospective participant reveals he has chronic bronchitis and typically requires supplemental oxygen when exercising. The participant has been walking regularly and independently but never monitors his blood oxygen levels (i.e., O2 saturation levels). In this case, the pulmonary condition dictates that the participant’s oxygen levels should be monitored before, during, and after exercise participation to ensure that O2 saturation levels are maintained. This individual would benefit by initially exercising in a clinic-based supervised exercise program, such as a supervised pulmonary rehabilitation or cardiac rehabilitation program (e.g., phase III). As with physician consent, there are no universal guidelines for referring an individual to supervised programs. Each exercise facility should have standards regarding the health conditions it considers itself qualified to supervise, and these standards should be based on the qualifications of its fitness professionals, the availability of medical equipment (e.g., supplemental O2, automatic external defibrillator [AED]), and its emergency preparedness (4). As always, fitness professionals should use their personal experience, as well as consultation with a supervisor or physician, to determine whether referral to a supervised program is necessary.

Key Point

The fitness professional should consider the participant’s health status, risk stratification, desired activity level, and fitness test results, in addition to the facility’s preactivity screening standards and emergency preparedness, to determine whether referral to a supervised exercise program is necessary.

Obtaining Physician Consent

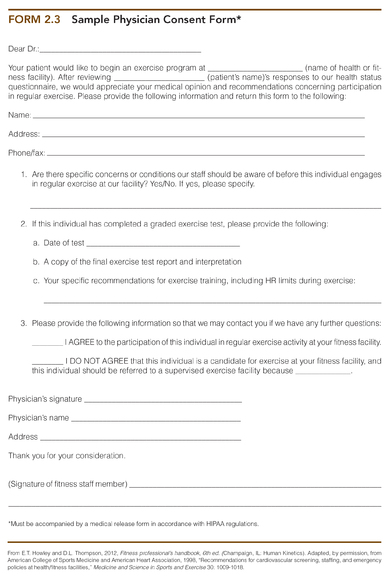

After determining that a person requires physician consent, the fitness professional should promptly inform the participant of this requirement. The appropriate medical personnel, typically the participant’s primary care physician, should provide the consent. A sample physician form is presented in form 2.3 (4). The form provides the physician with the option to refer the patient to a clinic-based supervised exercise facility. When a physician makes this recommendation, the fitness professional should contact the participant promptly and place him in contact with the nearest supervised exercise facility. In accordance with HIPAA regulations, the request for physician consent must be accompanied by a notation indicating that the participant understands that personal health information will be shared with appropriate allied health professionals. This permission is granted with the participant’s signature in the medical release section of the HSQ (15).

Physician consent can be sought in one of two ways. First, the participant can be given the paperwork to be signed by a physician. After consulting with a physician, the participant can return the paperwork to the fitness professional for verification. Second, fitness professionals can contact the appropriate physician directly (e.g., fax the consent form to the physician’s administrative office). Taking the initiative to contact a physician has both benefits and challenges. The following are benefits of taking the initiative:

- Demonstrates recognition of conditions requiring physician consent.

- Permits a relatively prompt reply from the physician.

- Acquires additional medical information so that the participant receives appropriate exercise testing and prescription.

- Builds rapport with local physicians conducive to obtaining future exercise referrals from them.

The workload of primary care physicians does not allow them to quickly respond to each medical request they receive. Thus, it is recommended to wait 3 business days before sending a second physician consent request. Thereafter, participants should be encouraged to contact the physician personally to expedite the return of the consent form. Participants requiring physician consent should be informed of the facility’s protocol for contacting physicians so that they understand that their clearance to begin exercising may take time. Although they may have to wait to exercise, participants should be assured that the steps taken in accordance with established protocols are serving their best health interests.

Key Point

The participant’s physician or appropriate medical personnel should be contacted immediately when physician consent is required for exercise participation.

To prevent the delay of fitness tests for individuals requiring physician clearance, the HSQ should be completed and furnished to the appropriate fitness professional for review 2 to 3 business days before a fitness test is scheduled. This will provide time to secure physician clearance and ensure that the appropriate paperwork is completed before the fitness test, allowing the participant to begin an exercise program shortly thereafter.

Education

All participants with documented primary risk factors or borderline clinical values for CHD should be provided with information about their increased risk for CHD, such as calculating their 10 yr CHD risk using the Framingham algorithm (16). In addition, the fitness professional should discuss sensible lifestyle changes that participants can pursue to more readily control their risk factors. However, information alone is unlikely to lead participants to make significant changes. Chapter 23 provides several approaches to changing behavior that fitness professionals can use to help the participant. In addition, the fitness professional can inform the participant of support groups, upcoming educational seminars, and other health professionals (e.g., dietitians) who can assist with healthy lifestyle choices.

Changing Health or Fitness Status

People who regularly participate in physical activity are likely to experience positive changes in their fitness and in their risk factors for CHD, such as greater CRF and lower resting BP. These changes can be readily observed by an increase in participants’ exercise duration or intensity and when resting BP measurements are taken. Changes such as these improve quality of life and reduce the risk for chronic disease (see chapter 1).

However, new medical conditions may develop and not be readily apparent after a participant completes preactivity screening and fitness tests. Unless specifically asked about new conditions, participants may not reveal this information. For instance, a participant may begin to experience chest pain during exercise but may keep this information private. The HSQ directs participants to contact the fitness director when they experience significant changes in their health status, but not all clients may understand the importance of this communication. Although some people will notify staff members when health changes occur, many will not. Therefore, periodic fitness retesting and readministration of the HSQ are advisable to determine whether participants experiencing changes in health status should seek physician consent or be assigned to a clinic-based supervised program.

If participants develop symptoms such as significant chest pain during exercise, they should be referred to a physician. In addition, participants initially classified as low to moderate risk who develop a medical condition that reclassifies them as high risk should be referred to a physician (1-3). Additional situations in which moderate- and vigorous-intensity exercise should be discontinued are musculoskeletal problems exacerbated with activity and severe psychological, medical, or drug or alcohol problems that are not responding to therapy (2). In addition, exercise should be deferred with major changes in resting BP (1). It is the responsibility of the fitness professional to determine the length of time between follow-up fitness tests or HSQ administrations to ensure participants are properly risk stratified and pursuing an appropriate exercise program.

Key Point

Fitness professionals should be aware of temporary or chronic conditions that alter a participant’s health status and warrant medical clearance, additional supervision, or changes in exercise recommendations. These conditions can be identified with periodic readministration of the HSQ and follow-up fitness tests.

Study Questions

1. What is the first step in the preactivity screening process, and what is its main objective?

2. When is it appropriate to use the PAR-Q versus the HSQ?

3. The categories of health appraisal can be recalled using the acronym MR. PLEASE. Provide a brief example of what each letter represents.

4. If a prospective exercise participant chooses not to complete a PAR-Q or HSQ, what is the next course of action?

5. Explain a sign or symptom that may indicate a participant has cardiac, pulmonary, or metabolic disease.

6. Section 3 of the HSQ addresses the identification of primary risk factors for CHD. Explain what a primary risk is and provide three examples, including the threshold for each.

7. Consider a 35-yr-old female who is 5 ft 6 in. (168 cm) and weighs 160 lb (72.6 kg), smokes occasionally on the weekends, and walks 3 days ? wk−1 for 35 min. Her HSQ indicates that she does not have high BP or cholesterol or type 2 diabetes. Her resting BP is 118/60 mmHg and her RHR is 85 beats ? min−1. What are her primary risk factors, and why did you designate them as such?

8. Why is it important to consider participants’ HDL-C levels when determining the number of risk factors?

9. What is an example of a chronic disease that puts an individual at high risk for cardiovascular complications during exercise participation?

10. Provide an example of an individual who would be at moderate risk for cardiovascular complications during exercise participation. When does this risk stratification require physician consent prior to exercise testing or participation?

11. Why is it important to review participants’ medications?

12. Why is it important to determine if a prospective exercise participant is physically active or not?

13. After obtaining fitness test results, what standards should the fitness professional compare them with?

14. Explain two scenarios in which a participant may be referred to a clinic-based supervised exercise program.

Case Studies

You can check your answers by referring to appendix A.

1. Barbara is a 48-yr-old female who has recently joined your fitness facility. She appears to be somewhat apprehensive as she taps her foot while you review her HSQ. After reviewing her medical history and determining her risk stratification, you conclude she can engage in unsupervised exercise. Next, you assess her resting measurements. Her resting HR is 112 beats · min−1 and BP is 158/94 mmHg. What do you do?

2. You are the instructor for a chair-based arthritis class that involves moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, stretching, and weightlifting and is open to the public. Everyone in the class completes a PAR-Q and answers no to all of the questions on the checklist. One of the participants is a woman of normal weight who mentions that she is 67 yr old when you speak with her. Upon further questioning, you find out she does not have any additional risk factors, and she walks 5 days ? wk−1 for 35 min at a brisk pace. She saw her physician recently for her annual physical and was given a clean bill of health. She recently read that resistance training would be good for her and therefore wants to attend your class. What are her primary risk factors? Do you permit her to participate in the class? Why or why not? What advice do you give her?

3. Tom, a 47-yr-old marketing agent who has been physically inactive for several years, visits your fitness facility to begin his fitness assessment. He has seen his physician recently and brings his lab results with him. Reviewing his HSQ, you note that he does not have a family history of heart disease. He is 5 ft 9 in. (1.75 m), weighs 185 lb (83.9 kg), and has a 38 in. (99.1 cm) waist. His resting BP is 124/82 mmHg and his resting pulse rate is 76 beats ? min−1. His blood chemistry values include a total cholesterol of 195 mg · dl−1, an LDL-C of 134 mg · dl−1, and an HDL-C of 40 mg · dl−1. (Consult table 2.2 for the defining criteria for CHD risk factors.). However, his HSQ states that he is taking medication for high BP and high cholesterol. His fasting blood glucose is 88 mg· dl−1, and he wants to pursue vigorous-intensity exercise.

a. Identify Tom’s risk factors for CHD and list the clinical threshold for each one.

b. Does he warrant physician consent before exercise testing and participation? Why or why not?