As an interdiscipline, ergonomics spans a variety of disciplines, including human anatomy, biomechanics, physiology, psychology, sociology, medicine, and engineering. Ergonomics is composed of three primary domains: organizational, cognitive, and physical. The organizational domain deals with organizational design, policies, and processes as they relate to workplace communication, work design and systems, networking, and teamwork. The cognitive domain involves mental processes, including perception, memory, reasoning, and motor response.

The physical domain is most relevant to our study of dynamic human anatomy. This domain integrates anthropometric, biomechanical, and physiological concepts as they relate to human movement, primarily in occupational settings. The principles of physical ergonomics have been used extensively in the design of consumer and industrial products, assessment of manual materials handling tasks, development of workplace safety guidelines, workplace design, and diagnosis of work-related medical conditions.

Goals

The primary goals of ergonomics are to improve productivity, improve efficiency, enhance safety, reduce injury risk, and reduce cost. Ergonomic interventions can improve both the quantity and quality of worker output and increase efficiency by facilitating production in a time-effective manner.

Safety enhancement and injury risk reduction are at the core of most ergonomic programs. One of the most common worker risks is a class of conditions collectively known as musculoskeletal disorders(MSDs). MSDs are the risk factor most closely associated with human movement tasks.

Research consistently has shown that ergonomic analysis and intervention can result in significant cost savings by reducing health care costs, lost work time, workers’ compensation claims, and human error. Many ergonomic interventions are relatively inexpensive and are therefore cost effective for businesses, agencies, and workers alike.

Many governmental agencies and professional organizations have issued safety guidelines addressing specific ergonomic issues and recommendations. These guidelines cover a multitude of industrial and service areas, including agriculture, apparel and footwear, baggage handling, computer workstations, construction, health care, product manufacturing, metalwork foundries, meatpacking, mining, poultry processing, printing, sewing, shipyards, and telecommunications (U.S. Department of Labor, n.d.).

Methods of Analysis

Ergonomic analyses can be reactive or proactive. A reactive analysis addresses an existing problem or situation. A proactive analysis seeks to anticipate potential problems and make changes that prevent these problems.

An ergonomic analysis typically involves several steps, the first of which is identification of risk factors. General risk factors associated with movement-related ergonomic problems include awkward postures, repetitive motions, forceful exertions, pressure points, and sustained static postures(NIOSH, 2007).

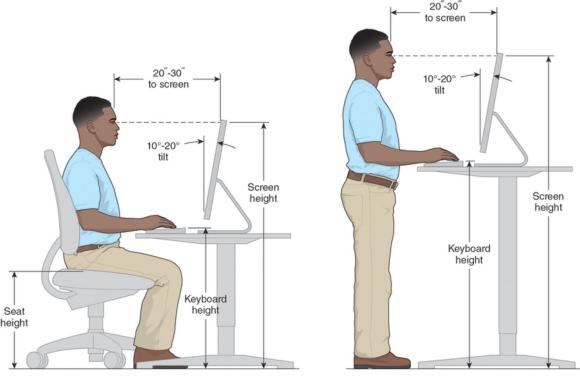

In conducting an ergonomic assessment, the first step is to identify risk factors specific to the situation being assessed. Risk factors may be systematic (i.e., evident in the overall work environment) or specific to an individual. In assessing the work environment of a computer data-entry operator, for example, potential risk factors might include keyboard height and inclination, monitor height (relative to the operator’s line of sight), distance, brightness, lack of arm and wrist support, chair design and support, and operator posture.

Once the ergonomic risk factors have been identified, the ergonomist must identify possible changes (e.g., new or adjusted keyboard, monitor, chair) to improve comfort and safety. After the changes have been implemented, the worker should be re-evaluated to ensure that the modifications have achieved the ergonomic goals.

Risk factors that are common to a group of workers can be addressed through either engineering or administrative controls. Engineering controls involve improving worker conditions by modifying tasks, adjusting movement patterns, redesigning workstations or tools, and providing protective equipment, as needed. Administrative controls include development and implementation of procedures and processes that can reduce risk such as job rotation (i.e., varying work tasks) and appropriate work breaks (e.g., rest or stretching breaks).

Numerous analysis approaches have been used to identify ergonomic problems and find solutions. Among those approaches are surveys and questionnaires, iterative prototyping, meta-analysis, work sampling, and a wide range of computer-based models applicable to specific tasks or systems.

Human - Machine Interface

Many occupations involve human interaction with a machine or device, in what is termed a human - machine interface. Examples include computer or keyboard operators (figure 13.1), assembly-line and construction workers, medical technicians and clinicians, and automobile mechanics.

Computer workstation anthropometrics for seated (left) and standing (right) operators.