When I began running in 1969, completing my first 42 km (26 mile) marathon in September 1972, we were advised to drink sparingly, if at all, during exercise. As I recall, that race provided only one “refreshment” station at 32 km (20 miles); there, our running times were also recorded, perhaps as proof that we had indeed been present at least at one point on the race course.

This approach had been followed ever since marathon running became an official event in the first modern Olympic Games in Athens in 1896. Until the 1970s, marathon runners were discouraged from drinking fluids during exercise for fear that it would cause them to slow down. For some, drinking during marathon running was considered a mark of weakness. My childhood running hero and subsequent friend, Jackie Mekler, five-time winner of the 90 km (56 mile) South African Comrades Marathon, described the drinking philosophy of runners with whom he had competed before his retirement in 1969: “To run a complete marathon without any fluid replacement was regarded as the ultimate aim of most runners, and a test of their fitness” (Noakes, 2003, p. 252).

Marathon runners were not alone in this belief. Cyclists in the race that was considered the ultimate physical challenge—the Tour de France—were advised similarly: “Avoid drinking when racing, especially in hot weather. Drink as little as possible, and with the liquid not too cold. It is only a question of will power. When you drink too much you will perspire, and you will lose your strength.” As a result only “four small bottles for a long stage (of the Tour), it was frowned upon to drink more” (Fotheringham, 2002, p. 180).

There is no evidence that this advice was especially dangerous, produced ill health or death, or seriously impaired athletic performance. Indeed, the most rapid improvements in marathon running performances occurred from 1920 to 1970 (figure 1, page xiv) in the period when athletes were not drinking much during races and were generally ignorant of the science of distance running, including the value of specific diets (Noakes, 2003).

A plateau in running times occurred after 1970. This effect is most apparent in the 42 km marathon, suggesting that all human runners, marathoners especially, are rapidly approaching the physical limits of human running ability. Note that in the period of 1900 to 1970, marathon runners were actively discouraged from drinking during exercise. The introduction and encouragement of frequent drinking after 1976 were not associated with any sudden increase in world-record performances in the marathon. Rather, an opposite trend is apparent (figure 1). The same trend exists also at the shorter–distance races, during which athletes do not usually drink.

The notion that athletes should drink during exercise took hold rather slowly. In November 1976 the prestigious New York Academy of Sciences (NYAS) held a conference titled “The Marathon: Physiological, Medical, Epidemiological and Psychological Studies” (Milvy P., 1977). The conference coincided with the first running of the New York City Marathon through the five boroughs of the Big Apple.

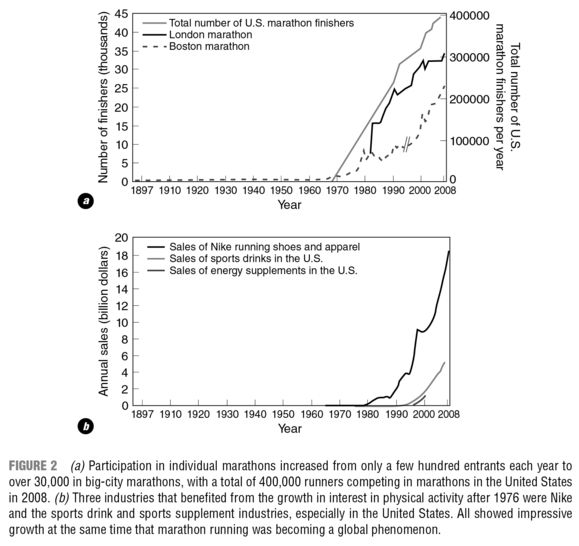

The race was a major success, launching the concept of the big-city marathons and stimulating an unprecedented growth in marathon running in particular and endurance sport in general. Thus, entrants in the New York City Marathon climbed from fewer than 2,000 in 1976 to more than 10,000 in 1980, reaching 30,000 by the late 1990s. Similar rates of growth were seen in the Boston and London Marathons, among many others (figure 2a).

No speaker at the NYAS conference on the marathon spoke exclusively on the role of fluid ingestion during exercise. Fluid balance during exercise was discussed only fleetingly because it was considered to be of little scientific relevance.

James F. Fixx, a writer from Riverside, Connecticut, who had begun running in the late 1960s—in the process losing 27 kg (60 lb) and completing six Boston Marathons—was an especially attentive attendee at the 1976 NYAS marathon conference. He came to acquire the medical and scientific information necessary for completing a book titled The Complete Book of Running (Fixx, 1977) that he had begun writing in April 1976. When published a year later, the book became an instant phenomenon, topping the New York Times best-seller list for 11 weeks and selling over a million copies. It was subsequently translated into all the major languages.

In The Complete Book of Running, Fixx wrote the following: “Drink lots of water while you’re exercising. It used to be considered unwise to drink while working out. Recent studies have shown, however, that athletes, including runners, function best when allowed to drink whenever they want to [my emphasis]. A 5 percent drop in body weight can reduce efficiency by 15 percent, and 6 percent is about the maximum you can comfortably tolerate” (p. 146).

Perhaps Fixx’s summary of the “state-of-the-art” guidelines gleaned from the 1976 NYAS marathon conference was that runners should drink according to the dictates of their thirst (“drink whenever you want to”) and should not lose too much weight during exercise since this causes an impaired “efficiency.” Interestingly, he made no reference to any dangers caused by dehydration in those who drank little and lost substantial amounts of weight during exercise. Rather, he reported that a loss of up to 6% of body weight could be “comfortably tolerated.” This confirms that Fixx did not hear anything at the NYAS conference or elsewhere proposing that runners should drink as much as tolerable in order to prevent any weight loss during exercise.

The sudden global growth in the number of marathon runners in Europe and North America soon generated a potential market for those selling products used by runners. James Fixx was himself perhaps the first to benefit through the sales of his book, unmatched by any subsequent book on running. Other beneficiaries would be Nike running shoes1 followed closely by the sports drink and nutritional supplement industries (figure 2b).

The Nike company born in 1972 soon became the maverick in the industry (Katz, 1994), selling not simply equipment but also an emotion. In 1978 the company published an ad claiming that excessive pronation (inward rotation) of the subtalar (ankle) joint was the cause of most running injuries to the lower limb. Naturally, Nike alone produced the solution to the problem—specially designed antipronation shoes. Sports doctors, including me, became disciples of this received wisdom (Noakes, 2003). In our naïvety we failed to question whether the advice was designed to sell more running shoes. Perhaps the fact that I received free running shoes from Nike South Africa for many years blunted my appetite for serious interrogation of their claims.

Only later (when my supply of free Nike running shoes ran out) would I begin to question whether excessive pronation is the cause of most running injuries. Indeed, it may play little role at all (see Noakes, 2003, pp. 767-770).

Writing this book has made me more aware of the effects of accepting even the most innocuous gifts from industry. How could a few dozen pairs of shoes over decades possibly influence my thinking? But it did. Because I was (and still am) a Nike guy. And Nike guys don’t question the hand that is feeding them the myth.